Cliff Rossi wakes at sunrise most mornings to the clamor of crab boats heading down Fishing Creek, a tributary off the Little Choptank River south of Cambridge, Maryland. His house sits roughly 100 feet from the shore. When he and his wife bought their home in Dorchester County more than two decades ago, they had to sign a disclosure alerting them to the local fishery’s hazards and noise disruptions.

Nobody mentioned the localized flooding that closes roads and traps some residents on the other side of the bridge when storm systems move up the coast. Yet, two decades ago such flooding occurred with much less frequency, rendering it much less disruptive and expensive.

“Few disclosures exist for any climate-related risk exposures,” says Rossi, a risk management expert whose expansive career in executive roles at government and business entities including the U.S. Treasury, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Citigroup, Washington Mutual, Countrywide Bank, and Radian Guaranty has landed him at the University of Maryland as director of the Smith Enterprise Risk Consortium. “Our real estate rules haven't yet caught up to this late-breaking risk that everybody's now focusing on,” he warns.

For increasingly more borrowers and homeowners across the United States, the American Dream of homeownership is underwater, up in flames, on ice, or in the wind. With housing costs at historic highs and inventory at historic lows, few people can afford to relocate. The accelerating frequency and severity of extreme weather events makes it increasingly difficult for homeowners across the country to afford to live where they do, though.

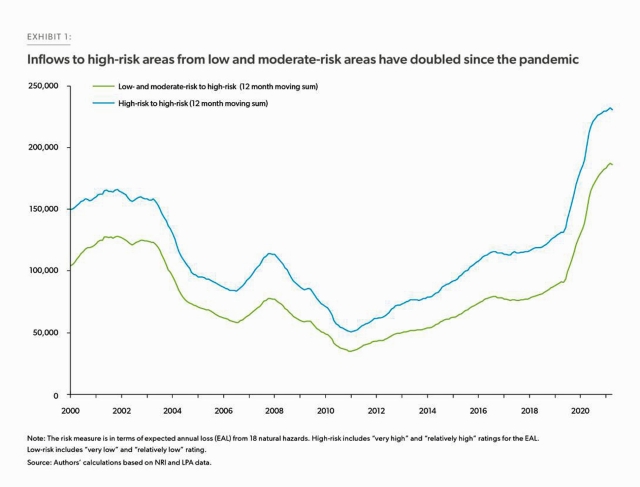

Research published by Freddie Mac in November 2022 shows migration to high-risk areas from low- and moderate-risk areas has doubled since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Housing and finance experts say few homebuyers know what kind of long-term risk their homes carry in light of accelerating climate change because the industry has not measured and priced that risk, nor have federal agencies charged with regulating the distribution of that risk.

Be it Phoenix, Arizona, southwest Florida, or coastal North Carolina, “fewer people should be moving to high-risk areas, whatever they may be chasing, like warmer weather or low taxes,” says Ted Tozer, a mortgage industry veteran who served as president of Ginnie Mae for seven years, actively managing Ginnie Mae's nearly $1.7 trillion guarantees of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and more than $460 billion in annual issuance. A non-resident fellow at the Urban Institute’s Housing Finance Policy Center and board member for PennyMac Financial Services, Tozer observes, “many of them don’t know that they are” buying and selling homes in high-risk areas.

A study published in September 2023 by First Street Foundation (FSF), a nonprofit that researches various socio-economic impacts of climate change, found 39 million properties in the U.S. face risks of rising insurance rates and non-renewals due to wildfires (4.4 million), wind (23.9 million), and flooding (12 million). A December study by the Foundation highlighted the rapid emergence of “climate abandonment areas” due to worsening extreme weather events.

However, housing and climate experts also fear a climate change-induced housing crisis would only progressively worsen as the underlying causes progressively worsened – more disasters, weaker resilience, plummeting values, skyrocketing costs. With the homeowners insurance markets already buckling in Florida and California, the nation’s largest and most-at-risk housing markets, whether the housing and finance industries will only diet and exercise after the heart attack remains to be seen.

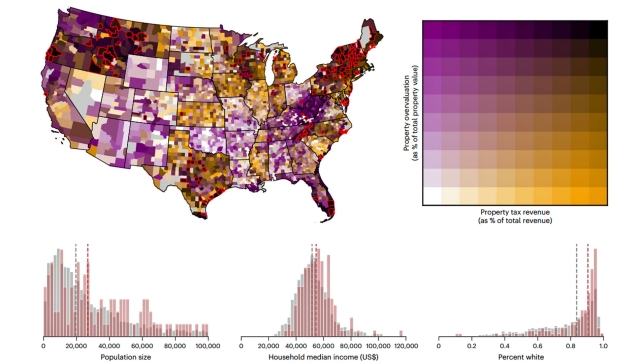

A peer-reviewed study published in Nature Climate Change in February 2023 outlines how climate change portends wholesale disruptions to the U.S. economy, impacting the employment and consumer debt levels fundamentally shaping cost and risk structures in mortgage finance. Deteriorating property values would hammer local governments relying on property tax revenues as the largest source of funding for government services. In 2020, property taxes accounted for 72% of tax revenues for local governments, according to the Tax Foundation. Slashing public services as property tax revenue plummets would push values downward, still.

One high-ranking federal climate officer who contributed to this story on the condition of anonymity says the complexity of accelerating climate change makes forward-looking mitigation efforts difficult to measure and implement. “You can't use the past as a predictor of the future,” the official said, when it comes to measuring and pricing climate risks.

“There's going to be some places, certainly, that if you look at the economics, the cost of home ownership is either going to go way up in those areas, or the value of the property is going to go down. That's the general mechanism,” the official explained. Pressed on how quickly rudimentary economics will translate into strategies for resilience – the past, in fact, being the best tool available for predicting the future – the official replied, “I think you're looking at a significant amount of time in order to get the whole United States at a level of resiliency for what we project to see.”

Toni Moss, founder and CEO of AmeriCatalyst, a residential real estate and business advisory firm, calls mortgages “the epicenter of the economic fault line.” Fifteen years ago, the collapse of the U.S. housing market led to the most severe worldwide economic crisis since the Great Depression. Moss was an early predictor of that crisis, alerting industry and government leaders as early as 2002 to the risk of economic collapse induced by failures in the mortgage industry.

Systemic climate risks, Moss warns, “we don’t return from.” Thus, in collaboration with CoreLogic, a market intelligence provider, AmeriCatalyst will be hosting officials from every relevant government housing agency – the FHFA, FHA, HUD, the Federal Reserve, the U.S. Treasury, the FDIC, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae – alongside housing, finance, and insurance executives, climate scientists, data analysts, academics, and various thought leaders at the “Going To Extremes” summit in National Harbor, Maryland, in mid-April, to collectively address this issue.

While “mass displacement” and “financial ruin” sound like distant, even overblown concerns in light of American exceptionalism, climate scientists across the world are in wholesale agreement that the earth will cross several global warming “tipping points” by 2030, just six years from now. As the impacts of climate change on the housing and finance ecosystem grow in frequency and severity, the requirements for resilience and expenses of recovery grow, too.

“Investing in resilience is far less expensive than paying for recovery,” Moss explains, and the numbers bear this out. No matter the expense of retrofitting America’s housing and finance industries for an increasingly unstable environment, “it is equally important to measure and quantify the cost savings of resilience,” she says. “For every $1 spent, you save $13.”

“It’s not getting better, it’s only going to get worse,” says Tozer. “Unfortunately, there’s no forum right now to talk about these issues,” which is why he will be in National Harbor in April.

Mapping Risk At The Census-Tract Level

“In the state of Maryland,” where Rossi lives, he explains, “they're big time on seeing this as a major issue. They would probably say this is a four-alarm fire.” As for the GSEs and the FHFA, Rossi senses their perceived severity of this issue ranks as a 4 out of 5; investors closer to a 3.

The Smith Enterprise Risk Consortium at the University of Maryland, where Rossi serves as director, is trying to raise awareness about these systemic climate risks. With the help of his Master’s students, Rossi merged the entire set of 2021 Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) loan data with the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) National Risk Index database, which maps assorted climate risks at the census tract level.

Their creation is the Mortgage Climate Risk Analyser (MCRA), a mapping tool that attaches severity scores to individual census tracts for various hazards, allowing users to toggle between property types, loan types, hazard types – even which government agencies have the largest exposure to certain regions, hazards, or loan types. The MCRA also assigns dollar amounts to potential losses in a given census tract, given the number of homes affected.

Depending on the filters selected, tables auto-populate with data like loan amounts, median incomes, median property values, and percentages of low- to moderate-income borrowers. The MCRA, which is currently being tested for quality control and loaded with 2022 HMDA data, will be hosted on Mortgage Bankers Association's (MBA) website as soon as April. A free version and a subscription version grant users the ability to measure the climate risk-footprint of their lending, borrowing, insuring, and investing decisions.

Though the MCRA does not track data to the individual loan or property level, Rossi says it is equally important to understand the risk facing whole communities as it is to understand the risk facing individual borrowers. “If all your neighbors are flooded out, but you’re not,” he says, “it's great that you're not flooded out, but imagine what impact that's going to have on your livability and on the property value that you face.”

However, making climate risks visible could also cause second-guessing on the part of borrowers who bought homes in high-risk areas and lenders who lend in those areas. A study published in the Journal of Environmental Economics and Management in 2005 found that after Hurricane Andrew (1992), undamaged homes in a neighboring county that were in flood zones saw a 19% decrease in price relative to those properties that were not in flood zones, but were also undamaged, in the same county.

While those findings suggest that home buyers revise their perceptions of risk after a major storm, it’s “buyer beware” until the risk is measured, mapped, and priced in. “I think it's more of a risk to the borrower than it is a risk to the seller,” Rossi says.

How Secure Is Secured Lending?

When it comes to unpriced climate risks in an increasingly unstable environment, Moss says the first question that needs to be answered is: how secure is secured lending in U.S. housing?

The operative assumption in any secured lending is that the loan collateral is secure. In mortgage lending, appraisals are the primary method of establishing the value of a mortgage loan’s collateral, the house. Appraisals mitigate “valuation risk” by establishing what value a lender may recoup if forced to take control of a property through foreclosure.

A secondary assumption in secured lending, however, is that the collateral will stay secure – that a house (and the land it sits on) will at least maintain its value until the borrower repays or defaults on the loan. In the primary market, where properties serve as collateral, and the secondary market, where borrowers serve as collateral as the funders of securitized mortgage bonds, insurance is the primary credit risk-transfer mechanism mitigating this “duration risk.”

The median age of owner-occupied housing stock in the U.S. is 40 years, according to 2021 American Community Survey data. Not only were the majority of U.S. homes designed and constructed in a different era and for a different climate, but so were the very financial instruments – mortgages – by which borrowers, originators, lenders, servicers, insurers, and investors buy and sell those homes.

Most U.S. mortgages are 15- or 30-year products, while insurance products only carry annual exposure. Environmental stability is part-and-parcel of any assumption around valuation risk and duration risk – that houses are worth, and will stay worth, what borrowers borrow, lenders lend, insurers insure, aggregators aggregate, and investors invest in those properties. The mismatch in duration risk is an assumption of environmental stability, Moss explains, bearing with it the assumption that affordable insurance will always be available.

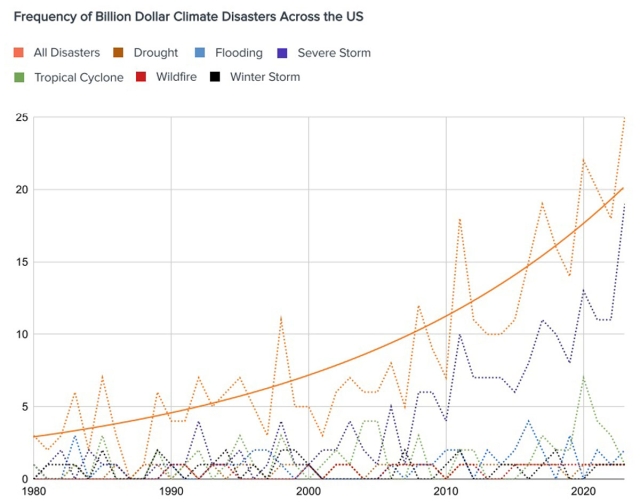

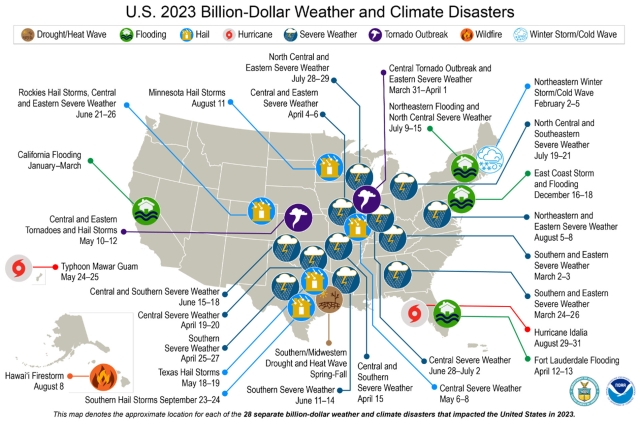

Since 1980 there have been 376 billion-dollar-or-more weather disasters in the U.S., according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The cumulative damages of those 376 events exceeds $2.655 trillion. Between 1980 and 2023, the annual average of billion-dollar events in the U.S. is 8.5. As evidence of accelerating climate change, the annual average from 2019 to 2023 is 20.4 events, with 28 billion-dollar disasters in 2023.

Federal Reserve data show the U.S. median home sale price has risen from $29,200 in the fourth quarter of 1972, to $479,500 in the fourth quarter of 2022. Median U.S. home sale prices have risen more than 22% since early 2020, and more than 48% since early 2009. Though home prices oscillate week-to-week and quarter-to-quarter, on the macroeconomic level, the collateral securing mortgage loans for the past 50 years has not only maintained a stable value, but dramatically risen in value.

Where secured lending and the assumption of environmental stability are concerned, the promise of ever-rising home prices has always been an effective hedge against durational risk exposure for borrowers, lenders, insurers, and investors. Unpriced climate risk threatens this fundamental assumption of housing finance: will homes in 2030, let alone 2035 or 2040, hold their value in an increasingly unstable environment, worth what they sold for in 2021 or 2022?

Unmitigated, Uninsurable, Uninhabitable

Where Tozer lives in North Carolina, insurers are in the process of requesting permission from state insurance regulators to increase premiums by 100% in coastal areas. Meanwhile, in-land communities are seeing their homeowners insurance premiums rise by 20-30% to offset the rising cost of insurers’ payouts along the coast.

“Everyone pays the cost of rising insurance,” he explains, referring to the cross-subsidization of rising homeowners insurance costs, not only in his own state, but across the country. He anticipates insurers will stop writing new policies in the high-risk areas of coastal North Carolina if requests to dramatically hike premiums are denied, as is “almost guaranteed” to happen.

As the rate at which extreme weather events occur quickens, insurers are finding it increasingly difficult to carry the accelerating costs of extreme weather events. The exodus of insurance providers from California and Florida is an indication that unmitigated climate change will make increasingly larger regions of the U.S. housing market as uninhabitable as they are uninsurable.

In California, insurers have been hiking premiums, not renewing policies, or pulling out of the state altogether. Alongside smaller providers, State Farm and Allstate have announced they will cease writing insurance for all personal and business property in California. State Farm was the state’s largest homeowners insurance provider, and Allstate the fourth-largest. USAA has also severely limited their coverage options in the state.

Florida, meanwhile, has been grappling with a deteriorating insurance market for two years, with three major insurers having withdrawn from the state: Farmers Insurance, Bankers Insurance, and Lexington Insurance, a subsidiary of AIG. AAA has stopped writing new policies. Numerous smaller, local insurers have simply gone insolvent or stopped writing new policies.

“If the insurance industry can’t make any money at risk-based pricing because they’re unable to price risk,” asks Moss, “are we taking climate change into account with our pricing on homes, bonds, mortgage servicing rights, guarantee fees? What would bond ratings or subordination levels look like if climate dynamics were factored in?”

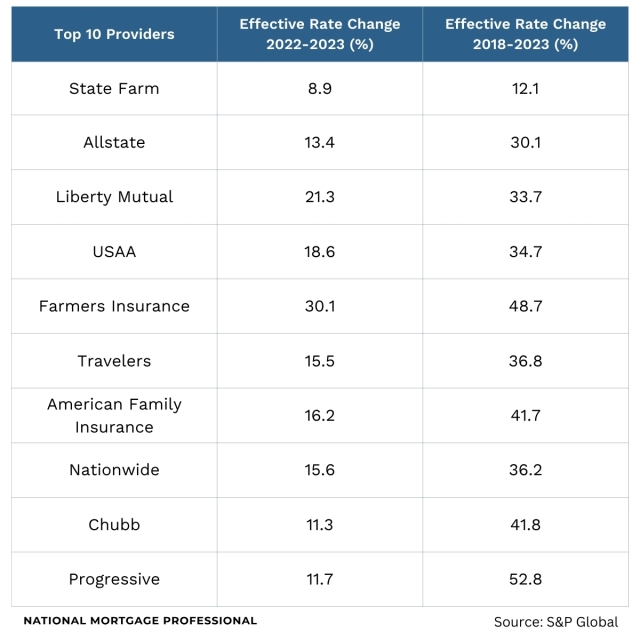

Data released in October 2023 by S&P Global, the market intelligence firm, show the effective rates for homeowners insurance from the top-10 providers in the U.S., who collectively underwrite nearly 70% of homeowners insurance policies nationwide, have increased anywhere from 12% to 52% over the past five years:

Though federal agencies and industry stakeholders are beginning to pay attention to the homeowners insurance crisis and adjacent unpriced climate risks, they are only in the data collection stage.

In a report published in September 2023 titled, “The Impact of Climate Change on American Household Finances,” the U.S. Treasury Department wrote, “further research is needed to better understand the full extent of the effects of climate hazards on housing and ramifications for household finances.” The Treasury’s Federal Insurance Office (FIO) announced in November 2023 that the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) would conduct a data collection project to assess the climate-related financial risks facing housing stakeholders nationwide.

Deputy director of Federal Housing Finance Agency’s (FHFA) Division of Research and Statistics and chairman of the FHFA Climate Change and Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Steering Committee, Dan Coates, told NMP of several climate-risk projects underway at the agency, such as a review of climate-change literature and an evaluation of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s exposure to natural hazard risk.

“We’re doing a study to look at how mortgage performance varies across different borrower demographics after a disaster,” Coates added, “and we’ve got a fourth study going on to look at the actual effects of natural disasters on house prices.” The impact of climate change on home prices is also of concern for Court Lake, a director in the US RMBS group at Fitch Ratings, who sees high home prices and “overvaluation” as a “significant driver of higher default risk.”

Fitch’s fourth-quarter, 2023 US RMBS Performance Report estimates that the national housing market is nearly 10% overvalued, which does not account for accelerating climate risks. “Environmental issues and costs related to insurance” are key data points the rating agency is beginning to measure, though they have only just started to pivot to this issue. Looking ahead, Lake says, Fitch anticipates accelerating climate risks to worsen consumers’ balance sheets “and actually, likely impact home prices.”

Disclosing Risk Raises Awareness

Whereas lightning rarely strikes twice in the same place, a home that has flooded before is bound to flood again. Yet, eighteen states – including Florida – have no statutory or regulatory requirements for disclosing a property’s flood risk or flood history to prospective buyers. Many states have only the bare minimum of flood disclosure laws, only requiring sellers to disclose a property’s location in a flood zone, not a property’s flood history, even if the seller has that information.

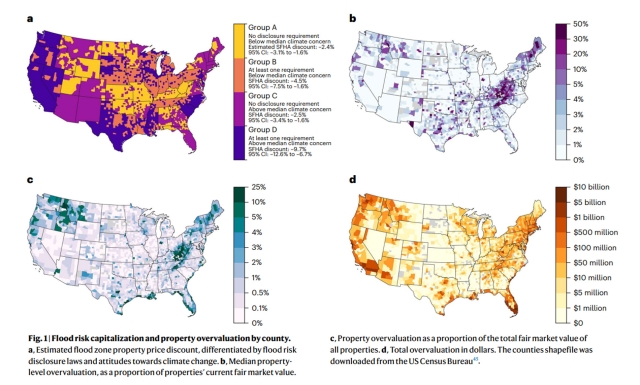

The peer-reviewed study in Nature Climate Change, referenced earlier in this article, found that residential properties exposed to flood risk are overvalued by anywhere from $121 billion to $237 billion nationwide, with much of that overvaluation concentrated in areas along the coast “with no flood risk disclosure laws and where there is less concern about climate change.”

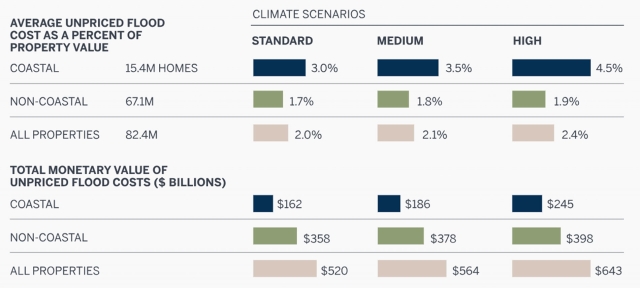

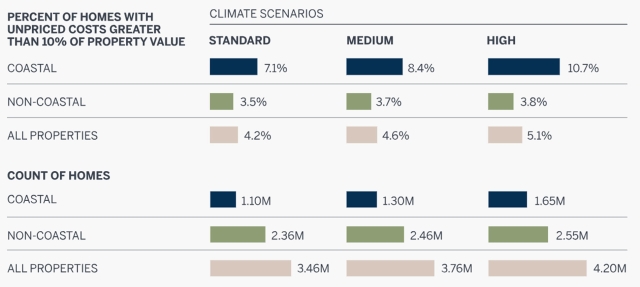

Another study, published in 2022 by Milliman, an actuarial and consulting firm, put flood-related overvaluations at $520 billion, finding that 3.5 million homeowners would face a property value correction greater than 10% if flood risk were priced correctly. Mortgage default exposure due to a repricing of flood risk could result in mortgage defaults increasing by up to 40% in a “high” climate change scenario.

Last year, FEMA introduced 17 legislative proposals that would, among other reforms, mandate certain flood risk reporting requirements for states to participate in the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). First implemented in 1968, the NFIP is an ungainly, underfunded federal program that grants homeowners access to low-cost flood insurance. Since the NFIP was last reauthorized in 2017, the program has experienced 27 short-term extensions, including three lapses, undermining the NFIP’s reliability.

Absent federal action, some states have adopted stricter flood disclosure laws of their own volition. Often, these laws are reactive, passed in the aftermath of disasters.

While flood disclosure laws in Louisiana and Texas are seen as models for other states, it took Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Harvey, the two costliest hurricanes in U.S. history, for those laws to happen.

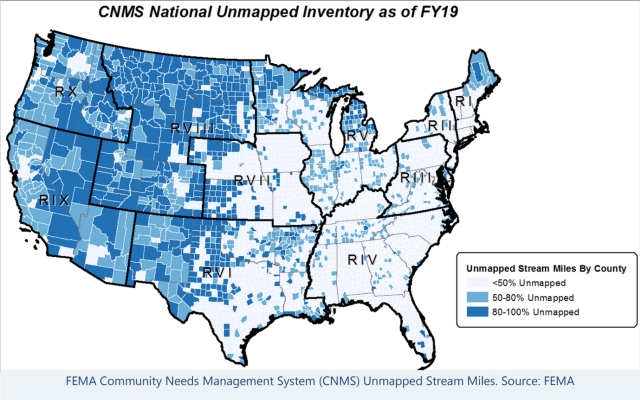

Undermining the utility of flood disclosure laws, however, is outdated and insufficient mapping of federal flood zones. High-risk areas that FEMA calls “Special Flood Hazard Areas” cover properties facing a 1% annual chance of flooding, requiring property owners with government-backed mortgages to buy flood insurance. FEMA officials testified to Congress that more than 40% of claims made to the NFIP from 2017 to 2019 were for properties outside official flood hazard zones, or in areas the agency had yet to map.

The Association of State Floodplain Managers reported in a 2020 cost analysis for completing and maintaining FEMA’s NFIP Flood Map Inventory that FEMA flood maps cover only 46% of shoreline and one-third of the nation’s 3.5 million miles of streams.

A 2017 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report found that half of the 166 counties in the U.S. facing the highest flood risk (based on available mapping) used flood maps more than five years old. Roughly 25% of those highest-risk counties used maps more than 10 years old – pre-2014.

Water-wise, though, the opposite of flood risk is drought risk. Where AmeriCatalyst’s Toni Moss lives in Austin, Texas, water usage costs have tripled in the last couple of years, she says. But, no one discusses drought disclosure laws. Nevertheless, such disclosures – whether for drought, flooding, fires, or hail – have the potential to be an essential tool for alerting borrowers and lenders to the costly climate risks lurking under and within the properties selling today.

The decades-long drought affecting the southwestern U.S. is well-documented, but since 2020, two little-known counties in Iowa have been experiencing the driest three-year period since the 1890s – drier than the Dust Bowl. Almost all of Iowa is experiencing some degree of drought, with a large portion experiencing “extreme drought,” the second most-intense classification.

Drought-stricken regions extend into parts of Kansas and Nebraska, as well, and without any rain, local officials say that the city of Caney in southeast Kansas will run out of water by March 1, this Friday.