In August, the 30-year, fixed mortgage rate hit the highest level since the early 2000s. Higher mortgage rates have a dual impact on the housing market – reducing affordability for potential buyers and strengthening the rate lock-in effect for sellers. The outlook for the U.S. housing market is therefore heavily dependent on the path of mortgage rates.

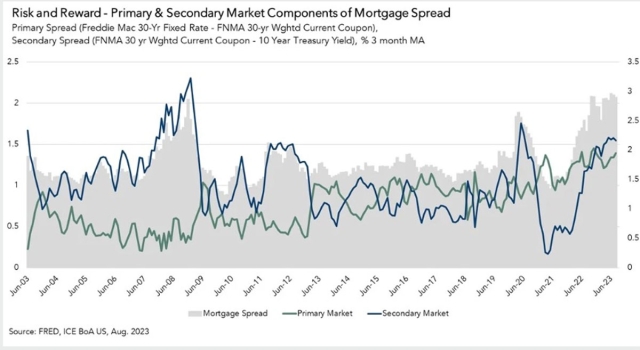

The popular 30-year, fixed mortgage rate is loosely benchmarked to the 10-year Treasury bond. Since the end of the Great Recession, the 30-year, fixed mortgage rate has on average remained 1.7 percentage points (170 basis points) higher than the 10-year Treasury bond yield. The spread in today’s market is closer to 3 percentage points. Many expect that mortgage rates will come down later this year, and that expectation is rooted in the belief that cooling inflation and more certainty about the outlook for monetary policy will result in a narrowing of the spread. However, some of the drivers of the widening of the mortgage rate spread will likely remain sticky, which may prevent mortgage rates from meaningfully declining.

The Components of the Spread

The spread between the 30-year, fixed mortgage rate largely reflects the risks associated with investing in mortgage-backed securities (MBS). That spread can be broken down into three components: primary, secondary and demand.

Primary: The primary component of the mortgage spread reflects the cost of issuing a mortgage, which for a conventional mortgage includes the annual guarantee-fee (g-fee), Loan-Level Price Adjustment (LLPA), servicing fee, and the lender revenue at time of loan sale in the secondary market (lender gain-on-sale). The primary component of the spread has historically stayed relatively stable, but has trended higher over the last decade. The mortgage rate paid by a borrower is split every month to pay the loan servicer for doing things like collecting the monthly payments, making interest payments to the MBS investor, and paying the GSE. Any remaining part of the borrower’s interest payment is usually converted to a one-time source of additional revenue to the lender as part of selling the loan, which is called gain-on-sale.

Secondary: The secondary component of the mortgage spread captures the prepayment, duration, and credit risk associated with investing in MBS. The secondary market component is the reason for the bulk of the increase in the overall mortgage spread since the beginning of 2022. Homeowners pay principal and interest every month and have the option to refinance their mortgage or sell their home at any time and pay off the loan entirely. That principal is “passed-through” to the investor and in the event of a loan pay off, the investor receives the principal and stops receiving the interest payments associated with that paid off loan. This is prepayment risk. And, when rates are changing quickly and it’s not exactly clear what the outlook is in the near term, it’s difficult to know how quickly or slowly that MBS will shrink over time. Investors need to be compensated for that risk relative to the “risk free” alternative.

The duration of the MBS is tied to the prepayment risk. The faster the prepayments, the quicker the principal is paid back and the shorter the “duration” of the MBS. The slower the prepayments, the longer the duration. The duration of an MBS tends to increase in a rising interest rate environment as there is less incentive for borrowers to move or refinance. The prepayment rate of the underlying mortgages typically slows down, which extends the life of the MBS and increases its duration. As a result, the spread between the mortgage rate and the 10-year Treasury yield may increase because the MBS investors require more compensation for the greater uncertainty associated with increased duration.

Credit risk is associated with the risk of default. At any point, borrowers can fail to make payment on the mortgage underlying an MBS. For agency MBS, the GSEs and Ginnie Mae promise full and timely payment of principal and interest, so there is no credit risk to an investor who buys agency MBS. But, if it’s non-Agency MBS, then the investor also needs to be compensated for the possibility that they won’t get all of the principal back.

Supply and Demand: Over the course of the pandemic, the Federal Reserve was a large buyer of mortgage-backed securities in the secondary market, generating demand that increased MBS prices and lowered yield for investors – this resulted in lower mortgage rates. Strong demand for MBS bids up the price and reduces the return the MBS investor receives, so the spread between the mortgage rate and the 10-year Treasury yield decreases. Now that the Fed has backed out as a buyer, there is less demand and that has contributed to the reverse – an increase in the spread.

What’s Next?

It’s possible that the spread will decrease when the Fed finishes its monetary tightening, which could be in the coming months. That would give investors some more certainty. And, if the spread narrows, then mortgage rates could come down even if the benchmark 10-Year Treasury stays the same. But the prepayment and duration risk will remain because so many homeowners remain rate-locked into much lower mortgage rates, and it’s less clear when the Fed may start lowering rates again, or what the “just right” federal funds rate level even is for this economy. Additionally, the Fed is unlikely to become a buyer of MBS again anytime soon. As a result of the sticky spread, it’s likely that mortgage rates continue to hover in the 6.5-to-7.5 percent range for the remainder of the year, which means affordability will remain a challenge for many home buyers.

Odeta Kushi is the deputy chief economist at First American.